Aunt Sammy: Shaping the Candies, Cakes & Wholesome Foods of Appalachia

You likely know Uncle Sam but probably not Aunt Sammy. So – allow me. She helped put Appalachian food on your table and mountain confections in your mouth! In 1926, she became a welcome part of the Appalachian and other farm, coal mine, and more general rural communities. She provided advice, news items and recipes on air and in print, many sent from thousands of listeners in rural communities, answering today’s question: WHAT IS real American cooking? She first appeared in 1926 as Uncle Sam’s (yes, that Uncle Sam) wife or sister (it isn’t entirely clear) – a true flesh and blood household advisor. Well, sort, of.

Who was Aunt Sammy? All about Betty Crocker & Friends: Candies, Casseroles, and Cake Mixes

To understand Aunt Sammy – and her relationship to Uncle Sam and the Appalachian homemaker – it’s important to know about Betty Crocker, Ann Pillsbury, Aunt Jemima, and the rising presence of radios in people’s homes in the early 1900s. Betty Crocker’s “life” as it was, started in the early 1920s, when General Mills created the woman who wasn’t. Betty Crocker was an even-keeled helpful household advisor and personality, designed to be as real as you and me. Betty had her own radio show, newspaper column, endorsements, and presence on the American landscape – but was actually played by a variety of actresses for decades. She was never outed and, even today, many consider her an actual person.

Marjorie Housted – One of the authors and voices called Betty Crocker

One of the many Betty Crocker faces

Betty Crocker wasn’t alone. She was joined by plenty of others including Ann Pillsbury, Aunt Jemima, and Carnation’s Mary Blake, all women who weren’t. These women also represented the interests of large businesses, promoting everything from flours and baking soda (using the sponsor’s brands) to cake mixes, where the company did it all. Their audience was middle class women, homemakers, and domestic help. And then there was Aunt Sammy!

Tune In Appalachia! Recipes, Advice, and A Good Friend on the Radio

Like Betty, Aunt Sammy’s presence rose up in the 1920s when radio’s rise in the American landscape was meteoric to say the least. At first, about 10,000 radios were on the American landscape, mostly homemade by radio hobbyist. Within five years, roughly 7.5 million people had a radio at home. For rural homemakers of Appalachia, radios were a link to the outside world, fueled by batteries, much more reliable than electricity, even in storms. Remember: rural homemakers were isolated on farms where they literarily made the homes, in charge of sewing clothes, growing, harvesting, and cooking food, raising kids, mending fences, and repairing whatever problem arose. Company? Little company, no television, no public transportation, and no newspapers. Even if they had newspapers, many of these women couldn’t read.

One of the friendly voices to break through the isolation was “Aunt Sammy” the wife of Uncle Sam. Unlike other advisors who represented the interests of corporations and, like Betty Crocker, focused on the middle class, Aunt Sammy represented the interests of the United Sates Department of Agriculture. Her audience was rural and town-based and her message was about many things, primary among them food. Good, wholesome, and economical food and using specific measurements and hygienic processes. In short, Aunt Sammy was bringing to rural communities’ recipes for better, healthier living – a first for a demographic others ignored.

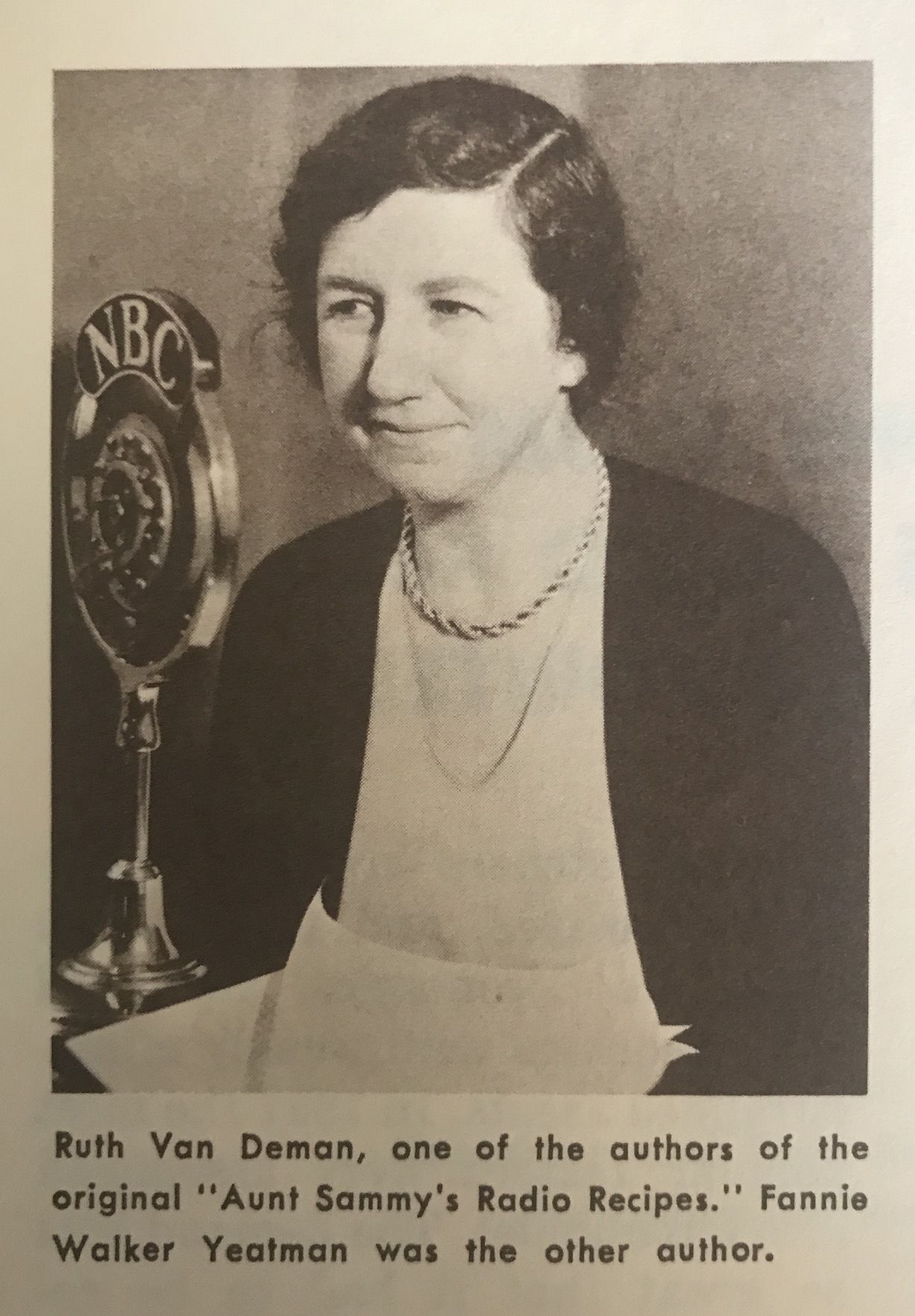

Ruth Van Deman, one of the authors of Aunt Sammy’s Recipes

Ruth Van Deman, one of the authors of Aunt Sammy’s Recipes

Listeners regularly tuned into Aunt Sammy’s productions which first aired five days a week in 1926, then called a variety of names – “Housekeeper’s Half-Hour” and “Aunt Sammy” among them. It was one of the first radio shows with regular characters, such as Ebenezer, an uncle; Billy, a nephew; Percy DeWillington, a fussy eater; and the Nosy Neighbor. Aunt Sammy was represented by 30 different women at 30 different stations – a total of 150 actresses over the years. They shared the same script, but, unlike Betty & company who were relentlessly the same, they had different regional accents. The reason: to gain the trust of listeners who welcomed them into their homes. Even the content was driven by letters sent by listeners.

By 1927, more than a million women were tuning into the program and had sent 60,000 letters seeking advice. If the questions were pertinent and interesting enough, they were raised on air. If not, the listeners received a personal letter in response. While the program covered a range of subjects, food was among the greatest places of concern.

Listening to Aunt Sammy of the Radio – Late 1920s

Hey Appalachia – Exercise Your Ingredients!

While radio was a miracle, and a useful miracle at that, it had flaws. It was scratchy and, at times, incoherent, a deficit when following recipe instructions. One production demonstrates the problem well, when a young husband was trying to copy a recipe for his wife. Unfortunately, the radio signals had crossed, and two shows – one, apparently an exercise show for men, and the other, Aunt Sammy, wove together. Still, the husband persisted, diligently taking notes, connections crisscrossing, and he ended up with the following instructions: “Hands on hips, place one cup of flour on the shoulders, raise knees and depress toes and mix thoroughly with one half-cup of milk…inhale quickly one-half teaspoon of baking powder, lower the legs and mash two hard-boiled eggs in a sieve…lie flat on the floor and roll the white of an egg backward and forward…”

Uncle Sam in Appalachia: Just Like a Man

As a supplement to the radio productions, Aunt Sammy joined the ranks of those producing cookbook/pamphlets in 1927. Simply called Aunt Sammy’s Radio Recipes, the instructions were simple, easy-to-follow and deemed fool-proof. Aunt Sammy promoted the cookbook on- air, saying: “By the way, some of you have begun to listen in quite recently. You may not have copies of the loose-leaf Radio Cook Book Uncle Sam is sending to homemakers. I want to give Uncle Sam all the credit due him, but the cookbook was not his idea at all. After he saw how neat it was, and how easily extra pages could be added, he waxed enthusiastic — he really did. His only regret was that he didn’t originate the idea himself. Isn’t that just like a man?”

Whatever Became of Aunt Sammy?

Within the first six months of publication, the USDA received 41,000 requests for the Aunt Sammy’s publication and soon had printed 100,000 copies. All were gone within the year. In 1931, a new edition called Aunt Sammy’s Radio Recipes Revised was released – also the first cookbook printed in Braille. In 1931, Aunt Sammy also instructed listeners in authentic traditional Chinese cooking techniques, helping to improve the quality of Chinese-American food prepared by home cooks. Her show continued to educate and stimulate rural homemakers in Appalachia and other areas through 1944.

——————————————————————————

Want to try Aunt Sammy’s recipes? You can find them here: Aunt Sammy’s radio recipes: United States. Bureau of Human Nutrition and Home Economics : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

TIRED OF THE SCREEN? Sit back, relax, and listen to Aunt Sammy, and get great food ideas as you do!: (2) Selections from Aunt Sammy’s Radio Recipes and USDA Favorites by Ruth van Deman | Full Audio Book – YouTube

——————————————————————————

We picked out a few easy-to-make options for Aunt Sammy’s fun foods – if you’re not up for cooking, you can get a variation from us. Her recipe book covers everything from meats to vegetables with plenty of helpful advice!

Pralines Recipe– A Classic

- 4 cups sugar

- 2 cups cream

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 3 cups pecan nut meats

Make a sirup out of 3 cups of the sugar and the cream. Cara- melize the other cup of sugar by melting it in an iron pan and stir- ring constantly with the back of a spoon. Into it pour all the sirup at one time, stirring constantly and rapidly. Add the salt. Boil the mixture to the soft-ball stage without stirring. Pour into a fiat pan and cool. Beat to a creamy consistency and add the nuts. Form into fiat, round cakes about 3 inches in diameter on a waxed paper. This amount makes about 20 cakes. During the creaming process the nuts must be added before the mixture shows signs of hardening. As this candy is to be in the form of round cakes, and not in a mass, work quickly to keep the candy from hardening before the cakes are placed on the waxed paper.

Try True Treats Pralines made in a Texas-based pecan plantation.

Sugared Popcorn Recipe – A Cousin to Kettle Corn

- Sugared Popcorn

- 1-1/2 cups sugar.

- 1 teaspoon salt.

- 1 cup water

- 2 quarts freshly popped corm

Cook the sugar, water, and salt until the sirup forms a soft ball when dropped into cold water, or until a candy thermometer registers 238° F. Remove from the fire. Beat with a spoon until it is creamy. Drop in the popcorn and Stir quickly until each kernel is coated with sugar. Put on a greased platter and separate the grains of corn. Cook the sugar, water, and salt until the sirup forms a soft ball when dropped into cold water, or until a candy thermometer registers 238° F. Remove from the fire. Beat with a spoon until it is creamy. Drop in the popcorn and stir quickly until each kernel is coated with sugar. Put on a greased platter and separate the grains of corn.

Turkish Paste Recipe

- 3 tablespoons gelatin.

- 1/2 cup cold water.

- 1 pound sugar.

- 1/2 cup hot water.

- 1/4 teaspoon salt.

- 3 tablespoons lemon juice.

- Green coloring.

- Mint flavoring.

- 1 cup finely chopped nuts

Soften the gelatin in the cold water for 5 minutes. Bring the hot water and sugar to the boiling point. Add the salt and gelatin, Stir until the gelatin has dissolved, and simmer for 20 minutes. Remove from the fire and when cool add the lemon juice, coloring, and mint flavoring. Stir in the nuts and allow the mixture to &and until it begins to thicken. Stir again before pouring into a wet pan and have the layer of paste about one inch thick. Let &and overnight in a cool place. Moisten a sharp knife in boiling water, cut the candy in cubes, and roll in powdered sugar.

The paste is 1/2 Turkish delight (circa 900 CE) and 1/2 Gum Drop which used Turkish delight as a prototype (originated around 1805, this version likely 1860s).

Nut Brittle Recipe

- 2 cups granulated sugar.

- 1 teaspoon vanilla.

- ¼ teaspoon salt.

- 2 cups nuts.

- ¼ teaspoon soda.

Heat the sugar gradually in a clean smooth skillet. Stir constantly with the bowl of the spoon until a golden sirup is formed. Remove from the fire and Stir in quickly the salt, soda, and vanilla. Pour the sirup over a layer of nuts in a greased pan. When cold, crack into small pieces.

The basic peanut brittle. Ours is from around the same time but uses corn syrup (an original American sweetener) and butter.

Parisian Sweets Recipe

- 1/2 pound figs.

- 1/2 pound nut meats.

- 1/2 pound dried prunes or seedless raisins.

Wash, pick over, and stem the fruits. Put them, with the nut meats, through a meat chopper, using a medium knife. Mix thoroughly. Roll out to a thickness of about one-half inch on a board dredged with confectioners’ sugar. Cut into small pieces; or make balls and roll them in confectioners’ sugar. If these sweets are to be kept for some tune, they should be put in a tin box or a tight jar.

Amazing – reminiscent of the early Middle Eastern fig cakes.

NECCO- Boston Early 1900s

NECCO- Boston Early 1900s

NECCO Last Stop in Masschusetts, Revere

NECCO Last Stop in Masschusetts, Revere

Ruth Van Deman, one of the authors of Aunt Sammy’s Recipes

Ruth Van Deman, one of the authors of Aunt Sammy’s Recipes

GOOD & PLENTY:

GOOD & PLENTY:

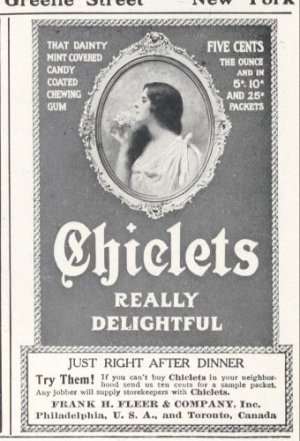

The Dubble Bubble has lived a long and fruitful life ever since, even appearing in the rations of GIs during World War II. It rose above competition from Topps, who made Bazooka just before the War and took off in the ‘50s, and Baloney made by the Bowman Company of Brooklyn New York, an early maker of trading cards. Today, Marvel Entertainment Group produces 15 million pieces a day. As for Frank Fleer – he died in 1921 and never lived to see his bubble gum succeed. William Diemer never trademarked his invention, never invented new confections, and never left the company. Instead, he became a senior executive and had a career which his wife said, after his death in 1998, was happy.

The Dubble Bubble has lived a long and fruitful life ever since, even appearing in the rations of GIs during World War II. It rose above competition from Topps, who made Bazooka just before the War and took off in the ‘50s, and Baloney made by the Bowman Company of Brooklyn New York, an early maker of trading cards. Today, Marvel Entertainment Group produces 15 million pieces a day. As for Frank Fleer – he died in 1921 and never lived to see his bubble gum succeed. William Diemer never trademarked his invention, never invented new confections, and never left the company. Instead, he became a senior executive and had a career which his wife said, after his death in 1998, was happy.